Course:Law3020/2014WT1/Group W

Odhavji Estate v. Woodhouse

Facts

Plaintiff was shot while fleeing from a bank robbery, plaintiff’s family brought at trial (Ontario Court General Division):

- Action against police chief was allowed to proceed (tort of misfeasance in a public office)

- Action against Metropolitan Toronto Police Services Board was not (tort of misfeasance in a public office)

- Action against the Province of Ontario was not (tort of misfeasance in a public office) for failing to ensure police officers involved were segregated, provided case notes, clothing and blood samples, and attended interviews with the SIU.

Statement of claim alleges mental distress, anger, depression and anxiety as a consequence of the alleged misconduct, but the plaintiffs will have to prove at trial that the alleged misconduct caused anxiety or depression of sufficient magnitude to warrant compensation.

Defendants also brought motion to strike out Plaintiff's statement of claim based on Rules of Civil Procedure, R.R.O. 1990, Reg. 194, r. 21.01(1)(b). (which was not successful)

Relevant Provisions

Action against Chief

Police Services Act s.41(1)(b):

41. (1) The duties of a chief of police include,

(b) ensuring that members of the police force carry out their duties in accordance with this Act and the regulations and in a manner that reflects the needs of the community, and that discipline is maintained in the police force;

Tort of misfeasance in a public office

"The failure of a public officer to perform a statu- tory duty can constitute misfeasance in a public office. Misfeasance is not limited to unlawful exercises of statutory or prerogative powers. It is an intentional tort distinguished by:

- deliberate, unlawful conduct in the exercise of public functions; and

- awareness that the conduct is unlawful and likely to injure the plaintiff.

The requirement that the defendant must have been aware that his or her unlawful conduct would harm the plaintiff establishes the required nexus between the parties. A plaintiff must also prove the requirements common to all torts, specifically, that the tortious conduct was the legal cause of his or her injuries, and that the injuries suffered are compensable in tort law.

Defendant's motion to strike out statement of claim

Rules of Civil Procedure, R.R.O. 1990, Reg. 194, r. 21.01(1)(b):

21.01 (1) A party may move before a judge,

(b) to strike out a pleading on the ground that it discloses no reasonable cause of action or defence,

and the judge may make an order or grant judgment accordingly. R.R.O. 1990, Reg. 194, r. 21.01 (1).

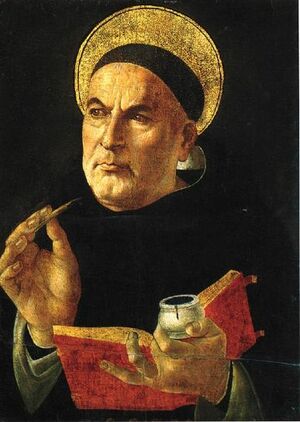

Natural Law - St. Thomas Aquinas

Natural Theory Law, as largely formulated by St. Thomas Aquinas, is chiefly concerned with law as it is linked to morality and the common good. Natural Law transcends time and human development, and derives from a higher, non-human source. For Aquinas, this source is divine. Subsequently, morality and ‘true law’ are seen as interchangeable in reality and synonymous in function. A ‘true law’ is adhered to, not because it was developed by human reason or evolvement, but because it is moral, just, and fair. As such, Natural Law exists and is followed to further the ‘common good’ as determined by morality. Teleologically, Aquinas saw morality and the ‘common good’ as essentially both the end and proper function of Natural Law.

The fundamental elements of Natural Law are:

- Directed to Common Good - Order Imposed By Law

- Follow Practical Reason

- Must be Made by Valid Lawmaker

- Must be Promulgated

Natural Law Application:

In the Canadian context, the theory of Natural Law as purported by Aquinas is not initially evident. For starters, a plethora of interpretations surrounding the ‘common good’ dot our diversified and individualized landscape. The range of political ideologies, religions, and personal convictions innately attribute to this. Nonetheless, in light of s. 52 of the Constitution and ‘Charter values’, Canadians, in a sense, enjoy a higher, transcendent source of law. As the ‘supreme law of the land’ the Constitution restricts statute and common law from being opposed to the ‘Canadianized’ version of the common good. Charter limits provide the means by which morality, justice and fairness are upheld to the utility of all. Any ‘unjust’ law not directed towards the common good purported in the Constitution can, and should, be struck down. While the principles of Natural Law are static, human-made laws develop over time and space to maintain relevance in society. Natural Law theorists would suggest these human-made directives must be in line with the principles of Natural Law, namely the ‘common good’, to be legitimate ‘true laws’. This falls in line with the Constitution, as the Natural Law in Canada, which allows for the development of new statute and common law so long as they align with its purpose.

In application to Odhavji Estate v. Woodhouse, the tort of misfeasance in a public office is a step towards aligning the common law with the Constitution . A logical analysis addresses the four fundamental elements of Natural Law in light of the 'Canadian common good'. To start, the tort of misfeasance of public office is aimed at holding public officials accountable to society, and maintaining the confidence of society in the executive branch. As such, the law is not directed to the good of a specific individual (public officials), but to the good of all. A prime example of the ‘rule of law’ in action, misfeasance of public office perfectly exhibits a law directed at the common good.

Secondly, Aquinas requires that ‘true laws’ follow practical reason. Here the common law must follow practical steps in fulfilling the ends purported by it, namely the common good. As stated by Iacobucci J, the tort for misfeasance in a public office carries a broad interpretation of “unlawful conduct in the exercise of public functions generally.” (para 17). Despite the expansive nature of this tort, Odhavji has provided two practical elements to be considered that direct public officials towards the common good. While not narrow or explicit practical steps, these two elements show what is required for the tort of public misfeasance, and point public officials as to what conduct should be avoided. They are as follows:

- “First, the public officer must have engaged in deliberate and unlawful conduct in his or her capacity as a public officer. Second, the public officer must have been aware both that his or her conduct was unlawful and that it was likely to harm the plaintiff.” (para 23)

It is likely, therefore, that Aquinas would agree with the common law tort of misfeasance in public office as following practical reason that direct society toward the teleological end of the common good.

Aquinas’ third element of a valid law requires a valid lawmaker. As his source of law is divine, Aquinas naturally attributes validity to lawmakers chosen and placed by God. With respect to Odhavji, a common law tort case, it is unlikely the judges as lawmakers would satisfy this requirement. The preference of a divinely chosen lawmaker is especially important considering that one lawmaker will very likely know what the common good (morality) is. On the other hand, a multitude of judges chosen by the people are unlikely to hold similar conceptions of the common good, likely forcing the creation of contradictory laws and interpretations. Given the vast broadness of this tort, and the room left for interpretation, it is even more likely Aquinas would invalidate this law as being ‘true’ Natural Law.

Finally, the law must be promulgated. While not a specific statute, the tort of misfeasance while in a public office is written in the common law and available to all. However, as the common law continues to make changes and progress (even if microscopically), public members that do not keep tabs on court rulings, or those unable to speak in legal jargon are left to a disadvantage. Therefore, as with the third step, it is likely Aquinas would be reluctant to consider this a ‘true law.’

Legal Positivism

Classical Positivism - John Austin

Austin's Three Directives

- God's law: "revealed" law; province of religion

- Positive morality: norms: manners, customs, club rules, international law, English constitutional law

- Has to be created in accordance with the rule of law making jurisdiction regarding the creation of law (pedigree test) (origin of the rule).

- Positive law: command, issued by superiors to subordinates, backed by sanctions

Post WWII Positivism - HLA Hart

Hart's Criteria

- Primary rules (tell us what is what isn't permitted)

- Secondary rules (rules that allow us to change the rules, adjudicate disputes about the rules, or figure out what the rules are)

- Rule of recognition (rules must be recognized by officials, must be applied by officials, and the officials must believe that they ought to apply them)

Positivist view is that laws are human artifacts, not dependent on moral content for validity, BUT disobedience may be warranted when laws are immoral.

Utilitarianism - Jeremy Bentham

Service Conception - Joseph Raz

Separation Thesis - HLA Hart

Hart’s Separation Thesis’ underlying theme is that law and morality are separate systems which have two different sets of rules and standards. Similar to legal positivists such as Austin, Hart believes law and morality should not be interchanged but should be kept distinct. However, he also seeks to distinguish the separation thesis from traditional legal positivism in that law and morality, although distinct systems, can interrelate with one another and will in fact usually run parallel to one another. What makes a legal rule legitimate is that it is grounded in the rule of recognition- meaning that the rule has to be recognized, applied and obeyed by the general populace. Such a rule is then considered to be backed by the legal system and is considered a ‘rule governed practice’ accepted by society.

Further, one of Hart’s main arguments is whenever there is a clash between the two systems individuals must decide whether the obligation to follow the moral rule is greater than the competing obligations under the legal rule. This argument derives from Hart’s intent to reconcile legal positivism with the public disfavour of traditional legal positivism in the Nuremburg Trials, which would have reconciled Nazi laws as legitimate despite being overwhelmingly immoral. Hart’s separation thesis will therefore instead that although recognizing Nazi Germany as valid laws, it would be unjustifiable for citizens or individuals to follow them.

Given this system, Hart understandably puts a great deal of responsibility and weight on judges as they are the ones that are applying these two distinct systems in their daily lives. Usually, it will be quite simple for the judges to just apply the legal rules in legislation and common law, as they have a ‘settled core of meaning’ of how to apply the ‘rule governed practice’ that is accepted in society. However, in some cases the facts will throw up a situation that falls outside the settled meaning into the penumbra. Hart calls these cases the hard case- where Courts have to apply ‘hard discretion’ to decide whether the case falls in the settled meaning. In applying their hard discretion, judges have to apply the terms of rule governed practices such as principles of justice and not principles of morality. The judge then applies these principles and terms of rule governed practice in the penumbra and either adhere with the settled meaning or make an exception to that settled meaning (as in exceptions in common law).

Application to Odhavji

This case would likely be deemed by Hart as a case in the penumbra. The appeal to the Supreme Court from the Police and the Chief of Police argue that by the standard of review the plaintiff has understood the tort of misfeasance all wrong and therefore his claims must be struck from the claim. The statute in this case, the Police Services Act, is not hugely disputed by the defendants, and Hart would agree that an appeal merely based on statute would not be a penumbra case as it is clearly stated what the duties of the Chief and the police are, and the consequences of failure to adhere to them. The core of this penumbra case is a dispute as to what the settled meaning of the tort of misfeasance in a public office is as interpreted by the plaintiff compared to how it is defined by the defendants. In such penumbra cases as Hart has indicated in his theory, judges have to apply discretion based on the terms of the governing practice such as principles of fundamental justice, and this is certainly what Iacobucci J seems to be doing.

The Court in this case ultimately ruled that the plaintiff by the standard of review has the right and the ability to bring a common law tort of misfeasance in public office against the police and the Chief of Police. Iacobucci J speaking for the Court relates how the tort of misfeasance in a public office came about and what the purpose of the tort was. The purpose of the tort is to protect citizens’ reasonable expectation that a public officer will not intentionally injure a member of the public through deliberate and unlawful conduct in the exercise of public functions. This is entirely consistent with the principles of fundamental justice which values public accountability, as well as tort law’s compensatory goals for punishing fault where it is due. Hart would argue that this decision is not reached by appealing to principles of morality, but that in applying the terms of the rule governed practice the principles of morality such as punishing wrongdoers and providing help to the victims merely overlapped with the terms.

Iacobucci J’s decision and writing for the Court would be entirely satisfactory for Hart in addressing whether the case would fit in the settled meaning of the tort of misfeasance in public office. Overall, it would seem that Iacobucci J’s approach would deem this penumbra case to fit inside the settled meaning of the tort while taking the opportunity to clarify the principles, how the tort can arise and the standards of proof required for proving liability by the plaintiff.

Fuller & The Morality of Law

Dworkin & System of Rights

Dworkin, mainly in response to positivism, rejected the idea that legal rules stood alone, separated from morality and principle. Rather, he submits a theory of the law espousing rules, policies and principles. Hart’s Separation Thesis suggested judges exercise extreme discretion in deciding penumbra cases by drawing on the terms of rule governed practice. Dworkin, on the other hand, believed judges were limited to (or should be limited to) rule within the bounds of legal principles which inform the law and exist outside of it. It is here that Dworkin rejects any suggestion that decision makers are pulled toward moral outcomes. Fuller, another adversary of positivism, wanted to maintain morality and suggested the judiciary would base their decisions on an outcome generating morality and social order. Dworkin rejects this view, suggesting the judicial process is influenced by the overarching principles, regardless of morality. These overarching (or underlying) principles are not bound by one ‘master rule’ or law, yet constantly inform the law and preside over it. In light of this, Dworkin advocates that a ‘right answer’ always exists. The judiciary, therefore, is left with the task to interpret, change, inform, or ‘find’ the rules infused within principles. ‘Hard cases’ (similar to cases which Hart would have described as being in the penumbra) where the correct rule is not initially evident require the judiciary to invoke principles, and perform such tasks. This means the amount of discretion left to judges is severely limited in contrast to Hart’s positivism. These overarching principles are to be constantly used by the judiciary to incrementally change rules so that they stay aligned with society’s conceptions of justice.

Policies, one of the three devices used in law, are social goals usually advocated by those in the political realm. Such goals, believes Dworkin, are to be left to the legislature but still have a profound impact on rules and principles. As social goals, policies generally try to reflect and represent the interests of a constituent body. As direct representatives of society, politicians and legislators are perfectly situated to advance and protect rights of groups and individuals. Dworkin holds that these policies may impact and mold underlying principles, thereby evolving the legal landscape through future application of the law. In the Canadian context, a prime example of public policy dictating legal principles and rules can be found in the Canadian Constitution and Charter. The rule of law, presumption of innocence, ‘peace, order and good government’, and civil liberties are all matters of public policy directly interacting and influencing the underlying principles in Canadian law, and subsequently it’s rules.

In application to Odhavji Estate, Dworkin would find little trouble with the Supreme Court of Canada decision. This is not a ‘hard case’, as the tort of misfeasance while in a public office had already been well established in Roncarelli v. Duplessis (Odhavji, para 19). The SCC explicitly discusses the tort of misfeasance in public office, and how it follows Canadian jurisprudence and underlying principles. The essence of this tort is said to “prevent the deliberate injuring of members of the public…. based on the rule of law” (para 26). The elements of ‘bad faith’ or ‘dishonesty’ in this tort “reflects the well-established principle that misfeasance in a public office” is inconsistent with Canadian values and policies. Not only has the Supreme Court of Canada reached a conclusion similar to existing jurisprudence, but has done so by drawing on the legal principles infused in our society. Dworkin would be well pleased.