Course:Law3020/2014WT1/Group W

Odhavji Estate v. Woodhouse

Facts

Plaintiff was shot while fleeing from a bank robbery, plaintiff’s family brought at trial (Ontario Court General Division):

- Action against police chief was allowed to proceed (tort of misfeasance in a public office)

- Action against Metropolitan Toronto Police Services Board was not (tort of misfeasance in a public office)

- Action against the Province of Ontario was not (tort of misfeasance in a public office) for failing to ensure police officers involved were segregated, provided case notes, clothing and blood samples, and attended interviews with the SIU.

Statement of claim alleges mental distress, anger, depression and anxiety as a consequence of the alleged misconduct, but the plaintiffs will have to prove at trial that the alleged misconduct caused anxiety or depression of sufficient magnitude to warrant compensation.

Defendants also brought motion to strike out Plaintiff's statement of claim based on Rules of Civil Procedure, R.R.O. 1990, Reg. 194, r. 21.01(1)(b). (which was not successful)

Relevant Provisions

Action against Chief

Police Services Act s.41(1)(b):

41. (1) The duties of a chief of police include,

(b) ensuring that members of the police force carry out their duties in accordance with this Act and the regulations and in a manner that reflects the needs of the community, and that discipline is maintained in the police force;

Tort of misfeasance in a public office

"The failure of a public officer to perform a statu- tory duty can constitute misfeasance in a public office. Misfeasance is not limited to unlawful exercises of statutory or prerogative powers. It is an intentional tort distinguished by:

- deliberate, unlawful conduct in the exercise of public functions; and

- awareness that the conduct is unlawful and likely to injure the plaintiff.

The requirement that the defendant must have been aware that his or her unlawful conduct would harm the plaintiff establishes the required nexus between the parties. A plaintiff must also prove the requirements common to all torts, specifically, that the tortious conduct was the legal cause of his or her injuries, and that the injuries suffered are compensable in tort law.

Defendant's motion to strike out statement of claim

Rules of Civil Procedure, R.R.O. 1990, Reg. 194, r. 21.01(1)(b):

21.01 (1) A party may move before a judge,

(b) to strike out a pleading on the ground that it discloses no reasonable cause of action or defence,

and the judge may make an order or grant judgment accordingly. R.R.O. 1990, Reg. 194, r. 21.01 (1).

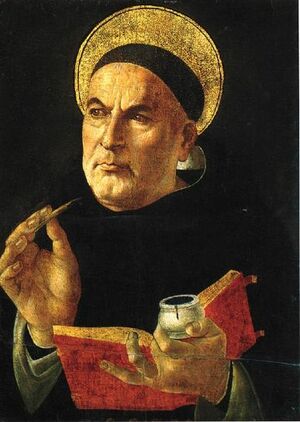

Natural Law - St. Thomas Aquinas

Natural Theory Law, as largely formulated by St. Thomas Aquinas, is chiefly concerned with law as it is linked to morality and the common good. Natural Law transcends time and human development, and derives from a higher, non-human source. For Aquinas, this source is divine. Subsequently, morality and ‘true law’ are seen as interchangeable in reality and synonymous in function. A ‘true law’ is adhered to, not because it was developed by human reason or evolvement, but because it is moral, just, and fair. As such, Natural Law exists and is followed to further the ‘common good’ as determined by morality. Teleologically, Aquinas saw morality and the ‘common good’ as essentially both the end and proper function of Natural Law.

The fundamental elements of Natural Law are:

- Directed to Common Good - Order Imposed By Law

- Follow Practical Reason

- Must be Made by Valid Lawmaker

- Must be Promulgated

Natural Law Application:

In the Canadian context, the theory of Natural Law as purported by Aquinas is not initially evident. For starters, a plethora of interpretations surrounding the ‘common good’ dot our diversified and individualized landscape. The range of political ideologies, religions, and personal convictions innately attribute to this. Nonetheless, in light of s. 52 of the Constitution and ‘Charter values’, Canadians, in a sense, enjoy a higher, transcendent source of law. As the ‘supreme law of the land’ the Constitution restricts laws from being opposed to ‘peace, order, and good government’ – the ‘Canadianized’ version of the common good. Charter limits provide the means by which morality, justice and fairness are upheld to the utility of all. Any ‘unjust’ law not directed towards the common good purported in the Constitution can, and should, be struck down. While the principles of Natural Law are static, human-made laws develop over time and space to maintain relevance in society. Natural Law theorists would suggest these human-made directives must be in line with the principles of Natural Law, namely the ‘common good’, to be legitimate ‘true laws’. This falls in line with the Constitution, as the Natural Law in Canada, which allows for the development of new laws so long as they align with its purpose. With regards to the common law, decisions by the courts, such as this one, are still informed

In application to Odhavji Estate v. Woodhouse, the logical analysis addresses the four fundamental elements of Natural Law in light of the 'Canadian common good' - 'Constitutional and Charter values'. First, the tort of misfeasance of public office is aimed at holding public officials accountable to society, and maintaining the confidence of society in the executive branch. As such, the law is not directed to the good of a specific individual (public officials), but to the good of all. A prime example of the ‘rule of law’ in action, misfeasance of public office perfectly exhibits a law directed at the common good.

Secondly, Aquinas requires that ‘true laws’ follow practical reason. Here the common law must follow practical steps in fulfilling the ends purported by it, namely the common good. As stated by Iacobucci J, the tort for misfeasance in a public office carries a broad interpretation of “unlawful conduct in the exercise of public functions generally.” (para 17). Despite the expansive nature of this tort, Odhavji has provided two practical elements to be considered that direct public officials towards the common good. While not exactly practical steps, these two elements show what is required for the tort of public misfeasance, and point public officials as to what conduct should be avoided. They are as follows:

- “First, the public officer must have engaged in deliberate and unlawful conduct in his or her capacity as a public officer. Second, the public officer must have been aware both that his or her conduct was unlawful and that it was likely to harm the plaintiff.” (para 23)

It is likely, therefore, that Aquinas would agree with the common law tort of misfeasance in public office as following practical reason that direct society toward the teleological end of the common good.

Aquinas’ third element of a valid law requires a valid lawmaker. As his source of law is divine, Aquinas naturally attributes validity to lawmakers chosen and placed by God. With respect to Odhavji, a common law tort case, it is unlikely the judges as lawmakers would satisfy this requirement. The preference of a divinely chosen lawmaker is especially important considering that one lawmaker will very likely know what the common good (morality) is. On the other hand, a multitude of judges chosen by the people are unlikely to hold similar conceptions of the common good, likely forcing the creation of contradictory laws and interpretations. Given the vast broadness of this tort, and the room left for interpretation, it is even more likely Aquinas would invalidate this law as being ‘true’ Natural Law.

Finally, the law must be promulgated. While not a specific statute, the tort of misfeasance while in a public office is written in the common law and available to all. However, as the common law continues to make changes and progress (even if microscopically), public members that do not keep tabs on court rulings, or those unable to speak in legal jargon are left to a disadvantage. Therefore, as with the third step, it is likely Aquinas would be reluctant to consider this a ‘true law.’

Legal Positivism

Classical Positivism - John Austin

Austin's Three Directives

- God's law: "revealed" law; province of religion

- Positive morality: norms: manners, customs, club rules, international law, English constitutional law

- Has to be created in accordance with the rule of law making jurisdiction regarding the creation of law (pedigree test) (origin of the rule).

- Positive law: command, issued by superiors to subordinates, backed by sanctions

Post WWII Positivism - HLA Hart

Hart's Criteria

- Primary rules (tell us what is what isn't permitted)

- Secondary rules (rules that allow us to change the rules, adjudicate disputes about the rules, or figure out what the rules are)

- Rule of recognition (rules must be recognized by officials, must be applied by officials, and the officials must believe that they ought to apply them)

Positivist view is that laws are human artifacts, not dependent on moral content for validity, BUT disobedience may be warranted when laws are immoral.