Difference between revisions of "Course:Law3020/2014WT1/Group D/Separation Thesis"

Checchiam13 (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

===Hart=== | ===Hart=== | ||

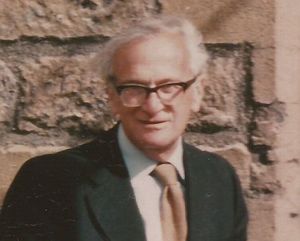

[[File:Herbert Hart.jpg|thumb|H.L.A. Hart]] | [[File:Herbert Hart.jpg|thumb|H.L.A. Hart]] | ||

| − | HLA Hart | + | |

| + | HLA Hart was an English legal philosopher at the forefront of the debate in the 20th century and arguably redefined the nature of law. The Concept of Law (1961) is his most notable work. He was a law professor at Oxford University and the principal at Brasenose College at Oxford. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In his Separation thesis, HLA Hart posits that morality and law should be separate. Rather than morality driving our obedience to laws, we have ought claims. Ought claims boils down to the proposition that the inner quality of a law is not morality, but rather a feeling we have that tells us we ought to follow them. This inner quality is what makes a law valid. | ||

| Line 14: | Line 18: | ||

===Fuller=== | ===Fuller=== | ||

| − | + | [[File:Lon4.gif|thumb|left|Lon Fuller]] | |

| + | |||

| + | Lon Fuller was an American legal theorist who, like Hart, discussed the connection between morality and law, which can be found in his work, The Morality of Law (1964). Fuller was a professor at Harvard University around the same time that Hart was a professor at Oxford and his debate with Hart can be found in the Harvard Law Review (Vol.71). This debate has helped frame the modern tension between legal positivism and natural law. Interesting to note, Lon Fuller was Ronald Dworkin’s professor at Harvard University. Ronald Dworkin would go on to write the System of Rights theory. | ||

| + | |||

| − | Fuller | + | In his work, Morality of Law, Fuller argued that social acceptance of legal rules relies on external morality which is the belief that they will produce good order. This external morality comes from the internal morality. Internal morality consists of the requirements that the rules be expressed generally, must be publicly known, must be prospective in effect, must be understandable, must be consistent with each other, must not require behavior beyond the powers of the affected, must not be changed frequently and they must be administered in a way that is consistent with their wording. |

| Line 46: | Line 53: | ||

Positivism requires two separate lines of inquiry. One looks to the validity of the law. The second line of inquiry looks to the morality of the law. Morality does not play a part in determining the validity of a law. This appears to be much like Hart’s separation thesis in that it takes morality out of the validity equation. | Positivism requires two separate lines of inquiry. One looks to the validity of the law. The second line of inquiry looks to the morality of the law. Morality does not play a part in determining the validity of a law. This appears to be much like Hart’s separation thesis in that it takes morality out of the validity equation. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| Line 56: | Line 60: | ||

Fuller, unlike Austin’s requirement of a political superior, political inferior and threat of sanction, requires a law to have an internal morality which in turn supports an external morality -the belief that the law will produce good order. Unlike Austin’s approach where the legislator is preferred to make decisions about the law and not judges because they are in an inferior position, Fuller believes that judge’s using their interpretation abilities to reference the internal and external morality of the law, will make the law what it ought to be. Fuller believes law is a collaborative effort between the legislator and the judiciary. | Fuller, unlike Austin’s requirement of a political superior, political inferior and threat of sanction, requires a law to have an internal morality which in turn supports an external morality -the belief that the law will produce good order. Unlike Austin’s approach where the legislator is preferred to make decisions about the law and not judges because they are in an inferior position, Fuller believes that judge’s using their interpretation abilities to reference the internal and external morality of the law, will make the law what it ought to be. Fuller believes law is a collaborative effort between the legislator and the judiciary. | ||

| − | == Case Study: Eldridge v B.C. == | + | == Case Study: [https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/scc/doc/1997/1997canlii327/1997canlii327.html Eldridge v B.C]. == |

In the Eldridge case, the issue concerns the protection of s.15 of the Charter involving equal benefit under the law without discrimination based on a disability is violated by the Medicare Protection Act. In other words, do the benefits determined by the Medical Services Commission, which are included under the definition of benefits in s.1 of the Medicare Protection Act violate s.15(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms because it fails to provide medical interpreter services for the deaf. This is a novel case which rests in the penumbra; the area surrounding the eclipse, which requires judges to apply the spirit of the law rather than the letter of the law. | In the Eldridge case, the issue concerns the protection of s.15 of the Charter involving equal benefit under the law without discrimination based on a disability is violated by the Medicare Protection Act. In other words, do the benefits determined by the Medical Services Commission, which are included under the definition of benefits in s.1 of the Medicare Protection Act violate s.15(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms because it fails to provide medical interpreter services for the deaf. This is a novel case which rests in the penumbra; the area surrounding the eclipse, which requires judges to apply the spirit of the law rather than the letter of the law. | ||

| − | The court, in applying their own reasoning, contradicts Hart’s conception of what a judge should do in a case. Justice La Forest provides a subjective interpretation that by granting discretion to the Medical Services Commission, the Hospital Insurance Act is in conformity with s.15 of the Charter. Justice La Forest states, “In my view, however, it is preferable to read the Act in conformity with s. 15(1)”( | + | The court, in applying their own reasoning, contradicts Hart’s conception of what a judge should do in a case. Justice La Forest provides a subjective interpretation that by granting discretion to the Medical Services Commission, the Hospital Insurance Act is in conformity with s.15 of the Charter. Justice La Forest states, “In my view, however, it is preferable to read the Act in conformity with s. 15(1)”<ref>''Eldridge v. British Columbia (Attorney General)'', [1997] 3 SCR 624 at para 32</ref>. This illustrates a process of interpretation and not simply enforcement of law. This subjective approach is also illustrated when Justice La Forest sets the standard for determining a prima facie breach of s.15 of the Charter <ref>''Ibid'' at para 81</ref>. This approach is more in line with what Fuller would argue is involved in court decisions: a collaborative effort between the legislature and the judiciary. Conversely, when Justice La Forest looks to precedent in regards to the interpretation of s.15 of the Charter, he is drawing on the rule governed practice which is in line with Hart’s thesis <ref>''Ibid'' at para 61</ref>. |

| − | When Justice La Forest distinguishes the court’s approach to interpreting what is integral to medical services from the lower court | + | When Justice La Forest distinguishes the court’s approach to interpreting what is integral to medical services from the lower court <ref>''Ibid'' at para 69</ref>, he is drawing from the moral belief of the system by determining that it should include coverage for the hearing impaired because the court has done the same in other cases <ref>''Ibid'' at para 54</ref>. |

| − | In determining which groups are subject to the Charter, and in turn whether the Commission should be held to it, Justice La Forest notes that s.32 of the Charter is general in the sense of who the Charter applies to. They determine that it applies generally to a category of government bodies | + | In determining which groups are subject to the Charter, and in turn whether the Commission should be held to it, Justice La Forest notes that s.32 of the Charter is general in the sense of who the Charter applies to. They determine that it applies generally to a category of government bodies <ref>''Ibid'' at para 40</ref>which follows Hart’s idea that law’s should be general and apply generally to a category and not specifically the individual. |

| − | When the court looks to adverse effect discrimination | + | When the court looks to adverse effect discrimination <ref>''Ibid'' at para 64</ref>, they are considering the moral beliefs of the system itself which is what Hart would argue for. Fuller, on the other hand, would argue the judges are applying there interpretation abilities to reference the inner and external moralities of the law and thus how the court should interpret s.15 and its protection of rights against the exclusion of benefits for interpreters. |

| Line 111: | Line 115: | ||

| − | In conclusion, Fuller would find that s.15 is violated by the Medicare Protection Act and would agree that the coverage for hearing impaired patients should be required. | + | In conclusion, Fuller would find that s.15 of the Charter is violated by the Medicare Protection Act and would agree that the coverage for hearing impaired patients should be required. |

| + | <div style="text-align: right;">[[Course:Law3020/2014WT1/Group_D/System_Of_Rights|Next: System Of Rights]]</div> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align: left;">[[Course:Law3020/2014WT1/Group_D/Positivism|Previous: Positivism]]</div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | {{Reflist}} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:22, 6 April 2014

Separation Thesis

Hart

HLA Hart was an English legal philosopher at the forefront of the debate in the 20th century and arguably redefined the nature of law. The Concept of Law (1961) is his most notable work. He was a law professor at Oxford University and the principal at Brasenose College at Oxford.

In his Separation thesis, HLA Hart posits that morality and law should be separate. Rather than morality driving our obedience to laws, we have ought claims. Ought claims boils down to the proposition that the inner quality of a law is not morality, but rather a feeling we have that tells us we ought to follow them. This inner quality is what makes a law valid.

He believed that when morality and law clashed, one must weigh the competing obligations in each case. Although law is not morality, it also does not supersede it.

Hart posited that legal rules are expressed in general words because they need to apply generally. We have general categories of people. This means that rather than the law applying to the individual because they are specifically that person, it applies to that individual because they fall into the category.

Hart does not believe judges apply moral rules in their judgments. Judges are drawing from the rule governed practice to decide on the hard cases that fall outside the settled core. These are cases where no applicable rule exists; the cases in the penumbra. So judges are enforcing laws and not interpreting them. This involves drawing on moral beliefs of the system itself which are fairness, justice and equality.

Fuller

Lon Fuller was an American legal theorist who, like Hart, discussed the connection between morality and law, which can be found in his work, The Morality of Law (1964). Fuller was a professor at Harvard University around the same time that Hart was a professor at Oxford and his debate with Hart can be found in the Harvard Law Review (Vol.71). This debate has helped frame the modern tension between legal positivism and natural law. Interesting to note, Lon Fuller was Ronald Dworkin’s professor at Harvard University. Ronald Dworkin would go on to write the System of Rights theory.

In his work, Morality of Law, Fuller argued that social acceptance of legal rules relies on external morality which is the belief that they will produce good order. This external morality comes from the internal morality. Internal morality consists of the requirements that the rules be expressed generally, must be publicly known, must be prospective in effect, must be understandable, must be consistent with each other, must not require behavior beyond the powers of the affected, must not be changed frequently and they must be administered in a way that is consistent with their wording.

For the law to have the external morality: to produce good order, Fuller agrees with Hart in that it needs to have an inner quality; however, unlike Hart, Fuller believes this is morality. Laws require this inner morality.

Fuller argued that the separation thesis does not adequately explain why we should obey the law since there is no answer to the dilemma of whether or not to obey unjust and immoral laws. He further claimed that Hart’s view that morality is potentially dangerous as a source of law, ignored the inner morality of law. He believes men should be required to explain their reasons because it will pull them to goodness.

Fuller would disagree with Hart in his position that sometimes morality will win in situations in which morality and law clash. Fuller argues that the separation thesis does not provide sufficient guidance in coming to a conclusion but rather is playing with word games and semantics. Rather, Fuller believes morality would win the day because for a law to be valid in the first place it requires morality.

Fuller contends Hart’s opinion of morality in law saying that the positivist and realist notion of morality is a straw man which is never really defined.

Fuller believes that judge’s using their interpretation abilities to reference the internal and external morality of the law, will make the law what it ought to be. Fuller believes law is a collaborative effort between the legislator and the judiciary.

Comparison with Other Theories

Contrast to Natural Law

Hart’s position contrasts natural law theory’s view of true law being derived from a non-human source which requires our human skill to find these laws, implying a universality of acceptance among society because they are natural. Hart does not believe that laws stem from God, but are to an extent universal because laws have an inner quality that we will recognize and feel we ought to obey. Both would agree that something inside of us lead us to the right legal rules but what that drive is is a point of contention for the two; natural law believes it is the common good which comes from God and Hart believes it is that inner quality but does not further explain where it comes from other than that it is not morality. Natural law, however, postulates that morality plays a role in our human law in that they must have a morally right aim.

This is contrary to Hart’s thesis of separating morality and law. Hart does not require that a law be made by a valid maker whereas natural law does. This valid law maker is someone who holds the position by natural order has and knows what the common good is. Natural law theory also holds that laws must be written. Natural law prefers legislation over judge made law because legislators possess the greater authority, are more likely to have the necessary wisdom and will not be moved by emotion. Hart understands that general laws will not cover every circumstance and there will be novel cases which fall outside the text of the law and therefore judges are required to provide the spirit of the law. This is the penumbra.

Where Fuller believes laws require a social acceptance based on the external morality which is the belief that the law will produce good order, natural law requires that the law be directed at the common good, follow practical reason, made by a valid law maker and be written. In rendering decisions, Fuller believes that judges are in a position to apply their reasoning, which includes morality. Natural law prefers the legislators to make laws over judges making decisions because judges are in an inferior position to legislators in making decisions about the law.

Contrast to Legal Positivism

Austin distinguishes between God’s revealed law –religion- , positive morality –customs, international law- and positive law –our legal rules. For a positive law to be valid it must be imposed by a political superior over an inferior and backed by threat of sanctions. The main distinction here to Hart is the requirement of a superior sovereign regarding the validity of law.

Positivism requires two separate lines of inquiry. One looks to the validity of the law. The second line of inquiry looks to the morality of the law. Morality does not play a part in determining the validity of a law. This appears to be much like Hart’s separation thesis in that it takes morality out of the validity equation.

Hart says that judges need to feel obligated to follow the law. This should not consist of a mindless approach. What they are doing is enforcing the law and not interpreting it. Austin claims that judicial decisions are commands and not general rule applying to a class. Austin believes Judges are subordinates that are acting as ministers with restricted authority from the state.

Fuller, unlike Austin’s requirement of a political superior, political inferior and threat of sanction, requires a law to have an internal morality which in turn supports an external morality -the belief that the law will produce good order. Unlike Austin’s approach where the legislator is preferred to make decisions about the law and not judges because they are in an inferior position, Fuller believes that judge’s using their interpretation abilities to reference the internal and external morality of the law, will make the law what it ought to be. Fuller believes law is a collaborative effort between the legislator and the judiciary.

Case Study: Eldridge v B.C.

In the Eldridge case, the issue concerns the protection of s.15 of the Charter involving equal benefit under the law without discrimination based on a disability is violated by the Medicare Protection Act. In other words, do the benefits determined by the Medical Services Commission, which are included under the definition of benefits in s.1 of the Medicare Protection Act violate s.15(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms because it fails to provide medical interpreter services for the deaf. This is a novel case which rests in the penumbra; the area surrounding the eclipse, which requires judges to apply the spirit of the law rather than the letter of the law.

The court, in applying their own reasoning, contradicts Hart’s conception of what a judge should do in a case. Justice La Forest provides a subjective interpretation that by granting discretion to the Medical Services Commission, the Hospital Insurance Act is in conformity with s.15 of the Charter. Justice La Forest states, “In my view, however, it is preferable to read the Act in conformity with s. 15(1)”[1]. This illustrates a process of interpretation and not simply enforcement of law. This subjective approach is also illustrated when Justice La Forest sets the standard for determining a prima facie breach of s.15 of the Charter [2]. This approach is more in line with what Fuller would argue is involved in court decisions: a collaborative effort between the legislature and the judiciary. Conversely, when Justice La Forest looks to precedent in regards to the interpretation of s.15 of the Charter, he is drawing on the rule governed practice which is in line with Hart’s thesis [3].

When Justice La Forest distinguishes the court’s approach to interpreting what is integral to medical services from the lower court [4], he is drawing from the moral belief of the system by determining that it should include coverage for the hearing impaired because the court has done the same in other cases [5].

In determining which groups are subject to the Charter, and in turn whether the Commission should be held to it, Justice La Forest notes that s.32 of the Charter is general in the sense of who the Charter applies to. They determine that it applies generally to a category of government bodies [6]which follows Hart’s idea that law’s should be general and apply generally to a category and not specifically the individual.

When the court looks to adverse effect discrimination [7], they are considering the moral beliefs of the system itself which is what Hart would argue for. Fuller, on the other hand, would argue the judges are applying there interpretation abilities to reference the inner and external moralities of the law and thus how the court should interpret s.15 and its protection of rights against the exclusion of benefits for interpreters.

The human rights legislation referenced to determine whether the Medical Services Act was required to take positive steps to ensure members of a disadvantaged group benefitted equally (para 79), is yet another illustration of how the court is drawing from the moral beliefs of the system and not simply applying subjective morality based on the whims of the judge.

How Hart Would Decide It

Hart would argue that judges have an “obligation” toward the law, fidelity in law in order to reach a decision that is consistent with the general conception of law. Determining which rights are included under the protection of s.15 of the Charter, it would be consistent to include a hearing impairment disability under the category of physical disability in s.15(2). A judge’s interpretation would involve drawing from moral beliefs of the system which include fairness and equality.

One could begin with an interpretation of s.15 of the Charter to determine if it is valid law because if it is not then there would be no law in which the Medicare Protection Act violates. As mentioned, according to Hart, a valid law is one that has the required inner quality. This inner quality is what drives our obedience. Hart argues this does not encompass our morality. Rather, it is what Hart calls “ought claims” which summons our obedience because we would have an inclination to feel that we ought to follow.

Under Hart’s separation thesis, the judges, drawing from the rule governed practice, would find that s.15 of the Charter is a valid law since it promotes fairness and equality which are aspects of the moral beliefs of the system itself. S.15 of the Charter also embodies the inner quality of an ought claim and would be validated by the majority of people seeing as the Constitution of 1982 was approved by Parliament; our elected representatives.

In determine whether the Medicare Protection Act violates s.15 of the Charter by not providing coverage for interpreters, Hart would find that the exclusion of interpreters for the hearing impaired renders the provision void of ought claims, in that it lacks that inner quality which is required for the law to be valid because it discriminates against an identifiable group, deaf people, by not providing benefits coverage for a necessary aspect to provide the required health care service of diagnosis, while providing other identifiable groups with coverage. This is in line with Hart’s belief that laws are made generally and apply to individuals because they fall into a group, and not because they are specifically that individual. The Medicare Protection Act is law that provides coverage for identifiable disabled minorities which a hearing disability should be included.

Assuming the Medicare Protection Act was valid; would the exclusion of the hearing impaired under the groups of which receive benefits be a violation of s.15 of the Charter? One could argue that the question of inclusion of one identifiably disabled minority into the Medicare Protection Act is a cross road of morality and law. Hart would argue that when morality and law clash, one must weigh the competing obligations in each case. Although law is not morality, it also does not supersede it. Weighing the obligations in this case and considering the finding through the separation thesis that the Medicare Protection Act is not valid law in that it does not have that inner quality because it discriminates against at least one group, morality would trump law and one would then determine how best to obey the law in light of this finding. In other words, the Medicare Protection Act would require the inclusion of the hearing impaired under the list of groups that receive benefits.

Hart would not save the definition of benefits under the Medicare Services Act under s.1 of the Charter because if it were to permit the discrimination of a minority, s.1 of the Charter would not have that inner quality that demands our obedience.

Fuller's Argument

As one would expect, Fuller would go about deciding this case differently than Hart. In examining s.15, Fuller would conclude that it is a valid law because it encompasses the internal and external morality requirements of what he considers a valid law. The inner morality here would be the protection of minorities through requirements of equality and restrictions against discrimination. This would work towards providing functional order since it is defensive and caring legislation providing for an identifiable group that society would agree could benefit from the protection of discrimination as opposed to a law oppressing a group which in turn could instil feelings of resentment and anger.

The external morality is established through the inner morality. Here, the inner morality provides the necessary belief that s.15 of the Charter would afford order. Fuller believes that the external morality is the acceptance of the law which is ultimately grounded in morality. Since s.15 of the Charter works to protect the identifiable minorities, this would be accepted as satisfying Fuller’s requirement of external morality. Fuller would conclude s.15 is a valid law.

In examining the Medicare Protection Act, Fuller would conclude that it lacks the external morality in the context of the Eldridge case because it discriminates against a group by failing to provide for the hearing impaired while explicitly providing for other identifiable minorities.

Through Fuller’s approach a judge would find that the Medicare Protection Act, by failing to provide for the hearing impaired, fails to be consistent with its purpose. This examination includes referring to the external morality and the law’s inner morality. The morality here would be providing coverage for handicapped minority groups so that they receive the treatment they require that is equivalent to the general individual. This morality is not met.

Assuming both the Medicare Protection Act and s.15 of the Charter were valid, the court in determining whether the Medicare Protection Act violates s.15 of the Charter under Fuller’s thesis would go about it differently from Hart’s Separation Thesis. A judge, under Fuller’s thesis, would find that s.15 of the Charter, in order to serve the purpose in which it was drafted, would be violated by the Medicare Protection Act because it discriminates against an identifiable minority, the hearing impaired and in turn does not promote equality.

Fuller would not save the law under s.1 of the Charter because in doing so would draw a conclusion that s.1 of the Charter, in practice, does not possess the internal and external morality required to be a valid law because it works towards an immoral end and therefore would defeat itself.

In conclusion, Fuller would find that s.15 of the Charter is violated by the Medicare Protection Act and would agree that the coverage for hearing impaired patients should be required.