Difference between revisions of "Course:Law3020/2014WT1/Group O/Separation Thesis"

Mcleodk132 (talk | contribs) |

Mcleodk132 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==''HLA Hart's Approach to the Separation Thesis''== | ==''HLA Hart's Approach to the Separation Thesis''== | ||

The Separation Thesis is a positivist claim grounded in the belief that law and morality are separate and distinct systems; which operate independently of one another. Hart believes that law’s authority is grounded in acceptance of the law as valid. Law is based on a system of “ought” claims. We chose to obey the law because we ought to. | The Separation Thesis is a positivist claim grounded in the belief that law and morality are separate and distinct systems; which operate independently of one another. Hart believes that law’s authority is grounded in acceptance of the law as valid. Law is based on a system of “ought” claims. We chose to obey the law because we ought to. | ||

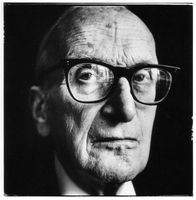

| − | [[File:HLA Hart.jpg|right|Caption]] | + | [[File:HLA Hart.jpg|300x200px|right|Caption]] |

Hart purports legal rules must be founded in a legal system. The strength of this system is based on society’s belief that the law is good law. Positivists argue that it is for the individual to decide whether the strength of their obligation to follow the law, outweighs their moral duty not to. | Hart purports legal rules must be founded in a legal system. The strength of this system is based on society’s belief that the law is good law. Positivists argue that it is for the individual to decide whether the strength of their obligation to follow the law, outweighs their moral duty not to. | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

===References:=== | ===References:=== | ||

| − | <div style="text-align: center;">JURISPRUDENCE</div> | + | '''<div style="text-align: center;">JURISPRUDENCE</div>''' |

Revision as of 16:24, 24 March 2014

Seperation Thesis and Morality of Law

HLA Hart's Approach to the Separation Thesis

The Separation Thesis is a positivist claim grounded in the belief that law and morality are separate and distinct systems; which operate independently of one another. Hart believes that law’s authority is grounded in acceptance of the law as valid. Law is based on a system of “ought” claims. We chose to obey the law because we ought to.

Hart purports legal rules must be founded in a legal system. The strength of this system is based on society’s belief that the law is good law. Positivists argue that it is for the individual to decide whether the strength of their obligation to follow the law, outweighs their moral duty not to.

Hart also speaks to the idea of the penumbra. For cases in which the meaning of terms is unclear or unsettled, judges look to the penumbra to decide these “hard” cases using rule-governed practices such as principles of justice. Hart uses the problem of the penumbra to illustrate the idea that laws are not related to a natural or moral belief, but to the meaning of the words.

The Morality of Law, Ron Fuller's Critique

Fuller, a critic of the positivist theory, contests that law and morality are intertwined. Fuller argues that social acceptance (i.e. rule of recognition) of the law is grounded in morality to produce good order. Another basis to Fuller’s view is that law has an inner morality; and when deciding “hard” cases Judge’s appeal to a morally independent standard. Fuller argues that the legal system, based on rational, consistent law can only be effective if judges and the legislature adhere to law’s “inner morality.”

Fuller in his attack of the Separation Thesis argues there is no “core settled meaning” and as such, no penumbra. Law’s are interpreted in context. Hard cases are those in which the outcome is uncertain. To determine good law judges create law how it ought to be. It is here we see the intersection between law and morality. Judges, in carrying out their duty, recognize that law is a collaborative effort.

Application to Case

In Alberta v Elder Advocates of Alberta Society, the Supreme Court of Canada must consider whether the relationship between the nursing home residents and Alberta Government is sufficient to raise a fiduciary duty. Arguably, this is a “hard case” which does not have settled meaning in law.

The concept of fiduciary duty aligns with Hart’s Separation Thesis. One ought to protect and owe a duty to those who are “vulnerable.” Yet, arguably this concept is neither moral nor grounded in morality. If it were, there wouldn’t be nearly as many restrictions or qualifications to raise this duty. It better suits “law” and applies to a limited number of circumstances that “ought” to be recognized.

As alluded, the penumbra problem arises here. The court was asked to create a new fiduciary duty. The specific duty sought related primarily to the setting of accommodation charges. The setting of accommodation charges is a purely regulative act undertaken by the legislature. It is not for the court to intervene in this process. To do so would overstep the court’s authority. As such, setting of the accommodation charges was left to the legislature with the court asserting that vulnerability alone is insufficient to raise a fiduciary duty.

If the concept of fiduciary duty was grounded in law and morality, as Fuller would propose, the court may have been more inclined to extend this duty. Yet surely this would not be “good” law or effective law, as it would extend the duty indeterminately. It cannot be said that the purpose of the legal system is to raise an indeterminate class of duties. This would flood the courts with unnecessary claims, diminishing efficiency and access to those truly in need.

A claim was brought under s. 15 of The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Charter is grounded in law and morality. The Charter upholds fundamental justice, a critical component to “law.” The enumerated rights ought to be protected. Similarly the rights the Charter seeks to protect are based largely on moral concepts. The Charter adheres to an “inner” morality.

Hart would argue that although moral principles underlie the Charter, that the Charter itself is not connected or intertwined with morality, as Fuller would propose. For Hart, the correlation between morality and law, as seen in the Charter, is due to the fact that often these systems run parallel.

S. 15 of the Charter protects against claims of discrimination. It is enshrined that every individual is equal before the law and will be equally treated under the law regardless of age, sex, gender and other listed grounds. This is fair and just, it is morally right. Canadian culture prides itself on inclusivity; a moral concept upheld throughout the Charter. It can be said that the Charter, broadly speaking, is aimed at an inner morality to produce good social order through upholding core rights.

The residents also brought forward an unjust enrichment claim. Yet again, we see an intersection between law and morality. An unjust enrichment claim is founded on three elements; (1) an enrichment of the defendant; (2) a corresponding deprivation to the plaintiff and (3) an absence of juristic reason for the enrichment.

The court held that we ought not to let the government arbitrarily increase accommodation charges. By overcharging residents, the Government used their money to partially offset their obligations without being entitled to do so. There was no juristic reason for the enrichment besides greed. The court held that the moral obligation to not engage in such activity was greater than following law.

Arguably, in deciding this “hard” case the judges appealed to their inner morality and allowed the unjust enrichment and s. 15 claims to proceed to trial.